Think it through

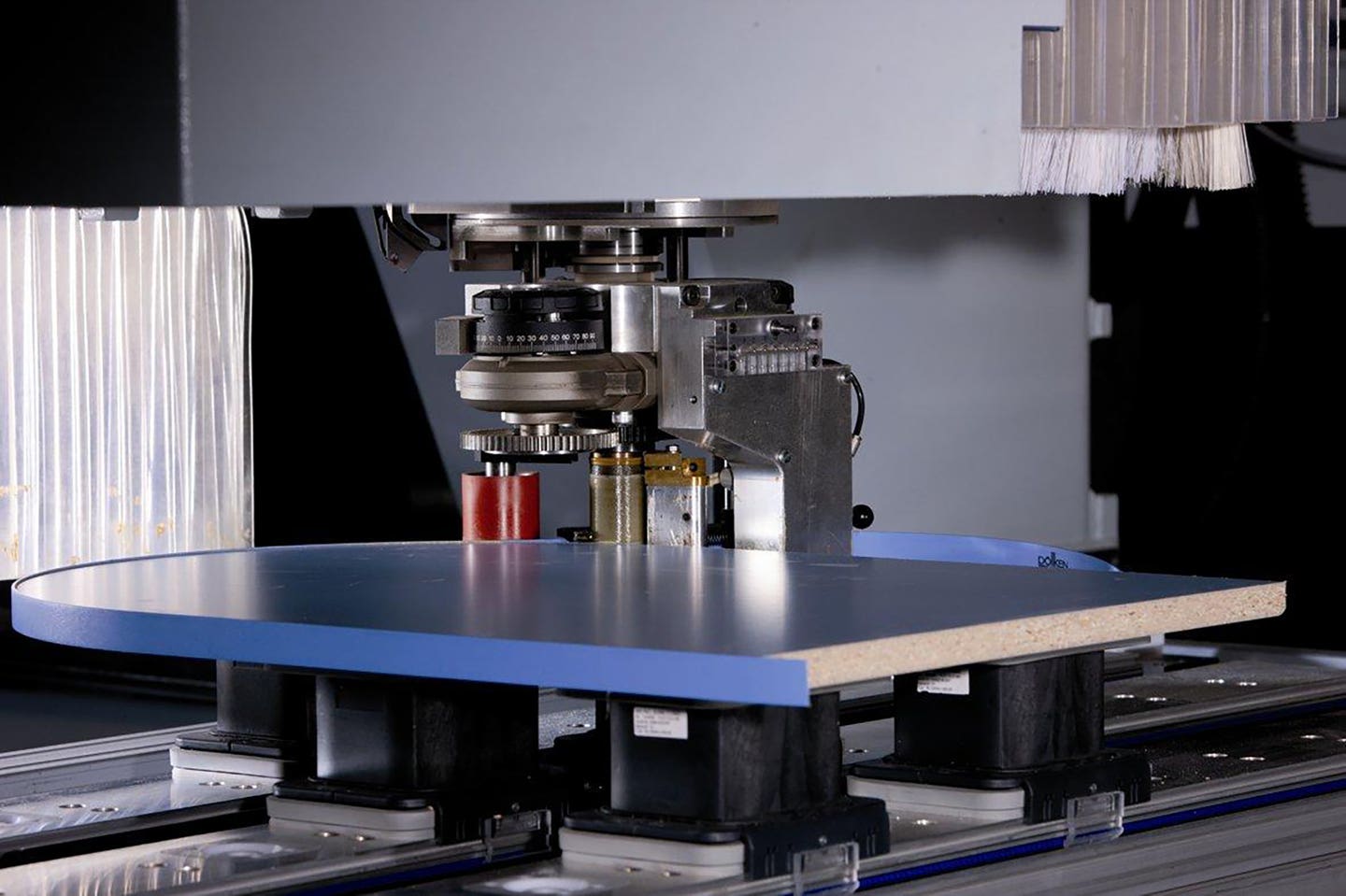

Investing in a 5-axis machine is a quantum leap for most woodshops, but the rewards include faster production, cleaner parts, more accuracy, and the ability to innovate

Woodshop owners who are considering the purchase or lease of a 5-axis CNC already have a pretty good idea of the machine’s abilities. This is by no means a small investment and most of the available options are very high-quality machines, so the choice isn’t as simple as choosing the ‘best’ one. It’s going to be about deciding which machine is best suited to the tasks that it will be asked to perform.

A 5-axis machining center can move a tool or a part in five different axes simultaneously. That’s a loaded sentence. Note that it can move either the work or the tool, or both, and also have more than one motion occur at the same time.

Small- and medium-sized shops that already operate a 3-axis machine are very aware of the limits of basic CNC operation. The process involves fixturing a part so it cannot move, and then having the machine move a single tool along one of the three fundamental axes – left/right (X), back/forth (Y), and up-down (Z). Machines with automatic toolholders still only chuck one tool at a time in the spindle. And 3-axis machines equipped with aggregate heads still operate by moving a tool to stationary work, even though aggregates do allow more angles for contact.

Do you need 5 axes?

A true 5-axis machine can rotate the work or the tool in two additional axes (A and B – more on these later). There is also the option of a 3+2 axis machine (also known as a 5-axis positioning machine), which offers standard 3-axis machining along with the ability to hold and rotate parts to a new stationary position between cuts. A 5-axis machine can work on moving parts. It can eliminate several clock-eating setups and can run a very complex cut on every area of a fixtured part except the bottom, and it can do so without stopping for parts adjustments. No matter how carefully and precisely a woodworker resets a part to provide access to new facets on a 3-axis machine, there will always be some minimal shifting. A 5-axis machine can deliver incredibly precise parts because each part is locked in place and is never moved.

A 5-axis machine can make some very complex parts such as curved stair bannisters or gently bowed automobile dashboards. And its complex ability to reach means that the cutter can almost always be perpendicular to the surface being milled, which of course reduces stress on the tool and allows for slightly deeper cuts and fewer time-consuming passes. That flexible reach can also let the machine use a shorter tool, which reduces vibration and drag, and delivers a more accurate and finished part that requires less sanding.

All of this adds up to a few basic questions that need to be asked before a shop even considers the various 5-axis machines available. Most importantly, if the woodshop is only building traditional casework, is there enough justification for the investment? A high quality 3-axis machine that is supported by knowledgeable staff and smart software can mill almost any part required in the manufacture of one or five-part doors and rectangular casework. For an occasional shaped part such as a decorative range hood or perhaps an island corbel, an aggregate head may be all that’s required. If the 5-axis machine is being considered based on volume and the ability to use a certain type of mechanical connection, would two 3-axis machines with aggregates be able to handle the work? That’s a valid question if demand ebbs and surges, where at times only one of the two machines has enough work to stay busy. It’s also a timely consideration if the industry doesn’t move past the current supply chain problems, where at least one machine might be kept alive when parts are in short supply. But if a shop is making complex parts, and lots of them, it awfully hard to argue against upgrading to five axes.

For shops that decide to upgrade, there are some basic concerns. The machine needs to be bulky and massive enough to handle hardwoods, MDF and plywood. Some 5-axis machines are built for delicate work such as making aluminum parts for planes, or plastic parts for signs and 3D advertising. A CNC that is making furniture or casework has to have a very robust spindle and toolholder, be dense and massive enough to dampen vibration, be powerful enough to maintain travel speed, and be smart enough to process data quickly and accurately. It should be compatible with the shop’s existing CAM and CAD software, or the shop needs to factor in new learning curves and costs there.

In-house maintenance is going to be a big concern. On most 3-axis machines, glitches can often be ironed out using phone calls, emails and Zoom. As the machine becomes far more complex, easy solutions are going to be more evasive. The employees who will perform maintenance and repair tasks are going to need more training. The manufacturer needs to offer 24/7 support because of time zone changes and second or third shifts in the woodshop that lie outside standard office hours. This is an all your eggs in one basket investment, and if it goes down it takes almost every aspect of production with it. The manufacturer should have distributors across the country with well-stocked spare part inventories, and a network of other customers nearby who can help in a pinch.

Getting up to speed

There is, of course, a learning curve once the decision has been made to upgrade, and that doesn’t just involve the machine operator. Designers are going to need to master some simulation software and build parts virtually before committing to a physical run. There are quite a few accidents in 5-axis machining where parts and tools and fixtures and even gantries collide because it was too difficult to visualize all the simultaneous movements. A computerized simulation can find these before they happen. Designers are also going to discover that many operations still only require 3-axis processing, and they’ll need to learn how to mesh those into sequences that take advantage of the machine’s 5-axis abilities. That will usually come down to running cost-analysis software that considers time as one of the primary integers. The other side of that coin is that one needs to consider when the 5-axis machine can eliminate setups, clamps, time spent handling parts, and time spent changing tools. Is it possible to keep the 3-axis CNC when the new machine arrives, rather than replacing it, at least through a transition period that provides an opportunity to quantify the benefits and costs?

When a shop invests in a 5-axis machine, the parts that it was purchased to make may need to be re-engineered. The fundamentals of the woodshop’s manufacturing process are going to be changed, so perhaps the geometry of the parts can also change. Nowhere it is written that a subassembly that previously had four or five parts still needs to be constituted that way. Now, that same subassembly might benefit from being milled as just one or two parts, because the new machine can reach into the work in different ways and at new angles and depths.

Enhanced abilities may also make it possible to create new variables for parts such as dimensional changes, or the locations of elements. For example, it may be easier to adapt an RV’s dashboard design to accommodate more dial options, or new electronics, or perhaps optional audio-visual elements without having to create a whole new design every time there’s an update from the client. That flexibility may also lead to a reduction in inventory and the static costs associated with stockpiling completed and raw parts. Because they’re so flexible, and require less setup and time, 5-axis machines can be quite adept at supplying just-in-time parts to a client who issues change orders.

Upgrading to five axes will also require a shift in tooling. Most machine upgrades will involve increased speed and torque, and consequently the shop will need to purchase a higher grade of tooling that is intentionally made for 5-axis machining.

Fourth and fifth axes

The heart and soul of a 5-axis upgrade is the addition of two new axes of rotation. One (called A) is around the X axis and the other (B) is around the Y. The machine can rotate either the tool or the part/table to access these two new abilities. Some machines swivel the tool and leave the part stationary (fixed table, moving gantry), which is a good idea when the parts are large. Other machines move the table (and the part that’s attached to it). In this case, the table might move left or right along the X axis, and then swivel toward the front of the machine on its A axis to reveal a different area/facet of the part that needs to be machined at a specific angle. Because the tool moves too, and constantly changes position so that it can address the part in the most perpendicular fashion, this much faster type of 5-axis action is known as continuous machining. Here it’s very important that the part is first made virtually in simulation software because the machine moves very fast, so collisions can be quick and catastrophic. But if the programming is done right, and the part is fixtured properly, and the tool is strong enough, and the operator has crossed his/her fingers correctly, this is the fastest way to manufacture multiple complex parts. There are few or no adjustments and interim setups to make, so the net result is better, more accurate parts made in less time.

If only one of these new axes will be required, it’s a good idea to contact the manufacturer of a shop’s existing 3-axis machine and ask whether a fourth axis can be added. There are also some 4-axis machines available on the market that essentially turn the X axis into a CNC wood lathe. They tend to be a bit smaller, but they can be surprisingly affordable compared to a true 5-axis machine.

One of the core values in 5-axis machining is technical support. It’s essential to research customer reviews, contact shops that already own the machine, and visit online user groups to get an accurate assessment of how well the manufacturer stands behind the machine. This isn’t about product support where failed parts are serviced or repaired. With machines this complex and expensive, that’s rarely a problem. This concern is about how the manufacturer will work with the woodshop during the initial learning curve, and what intellectual resources are going to be available as new uses are found for the machine. Keep in mind that CNCs serve a lot of industries, so it’s important that the manufacturer of the machine that is being considered by a woodshop has specialized expertise and experience in the woodworking field. Plastics and metal don’t behave like solid wood and sheet stock.

Another aspect of support is integration. Depending on the CNC manufacturer, the machine could be part of a larger management software environment that includes machine maintenance and performance monitoring. It may also be linked to other work cells such as edge-banding or coating, or perhaps to automatic loading and unloading. Some of the software can cross platforms or integrate into even larger management software packages that monitor shop workflow, inventory, personnel, and other aspects of the business. Those programs have acronyms such as ERP, PIM, MDM and PCM. Depending on how automated the woodshop is now, and also what’s planned for the near future, it may be critical to find out how well a new 5-axis CNC will play with the other children in the shop.

Some questions to ask

Technology is moving fast. How adaptable will the machine be to future advances in the mechanics of spindles such as better cooling and dust collection, or to technology leaps in concepts such as the Industry 4.0 envelope or lean manufacturing? Can it grow as the shop’s demands grow?

Can all five axes on a potential new machine be moved simultaneously? Sometimes there are controller or software issues, rather than hardware restrictions, that prevent this. And does the shop actually need all five motions simultaneously?

Another core consideration is the nature and physical size of the products being made in the woodshop. The Z axis travel can be more critical than the machine’s table dimensions for 3D parts. Some manufacturers offer the option of increasing the Z clearance (a taller gantry), and this can be worth exploring.

Depending on the spindle size, the nature of the tooling and the dimensions of the parts, it may be possible to reorient projects that have traditionally been made on a 3-axis machine so that they present to the new and nimbler 5-axis spindle in a way that doesn’t require as much height, or that requires more height for faster processing. Keep in mind that less massive machines may have an issue with stability or vibration as the gantry gets taller.

Does the shop need a full-scale 5-axis machine? If the intent is to add the ability to make complex parts rather than to increase the rate of production, there are several small and affordable 5-axis machines on the market that may be able to bridge that gap. Be aware that many smaller machines are intended for sign-making in foam or ABS, so they may not have the rigidity to machine hardwoods. If possible, a shop could have the machine manufacturer mill some parts before a purchase is finalized, while the woodworker watches and evaluates the process.

The bottom line here is growth. Technology-based businesses such as high-end production woodshops are like some species of sharks: if they don’t keep swimming forward, they die. Investing in a 5-axis machine is a quantum leap for most woodshops. Whether it’s new equipment or used, and bought or leased, the time commitment and the learning curve are as big a consideration as the monthly payments.

After the cost-benefit analysis is done, the decision is made and the machine is selected, there’s one more aspect of purchasing that might require a little more thought right now than it used to. Inflation has been creeping back into the general economy, and that usually goes hand-in-hand with higher interest rates. Variable rate loans are never a great option for purchasing plant and machinery, and the slightly unsettled nature of the world economy with issues such as Covid and supply chain problems suggests that this might be an opportune time to explore leasing as an option.

If a woodshop can justify the purchase, the machine will revolutionize the production cycle and impact almost every aspect of the business from personnel to purchasing. The scale of, well, everything in the shop will increase. Some tasks will become more specialized while others will disappear. Upgrading to a 5-axis CNC is an exciting and sometimes anxious leap of faith, but the rewards include faster production, cleaner parts, more accuracy, and the ability to innovate both products and production processes.

This article was originally published in the February 2022 issue.