The rabbet habit

I’ll use whatever joint is best for a project, but when given free reign I’ll almost always choose a rabbet joint.

I’ll use whatever joint is best for a project, but when given free reign I’ll almost always choose a rabbet joint.

If it’s a utility project, butt joints along with fasteners might be fine. If it’s to make an exact reproduction or to really show off your skills, you could cut dovetails. For shear strength and weight bearing, a mortise-and-tenon joint may be best.

But if you just need a strong basic joint that’s easy to cut and quick to assemble, for my money you can’t do better than a rabbet joint.

Increased gluing surface, self-squaring, very strong and able to be created with a variety of tools, the rabbet joint has to be the most versatile. Drawer boxes, shelving, cabinetry, panel insets, picture frames, and dozens of other applications work extremely well with rabbets.

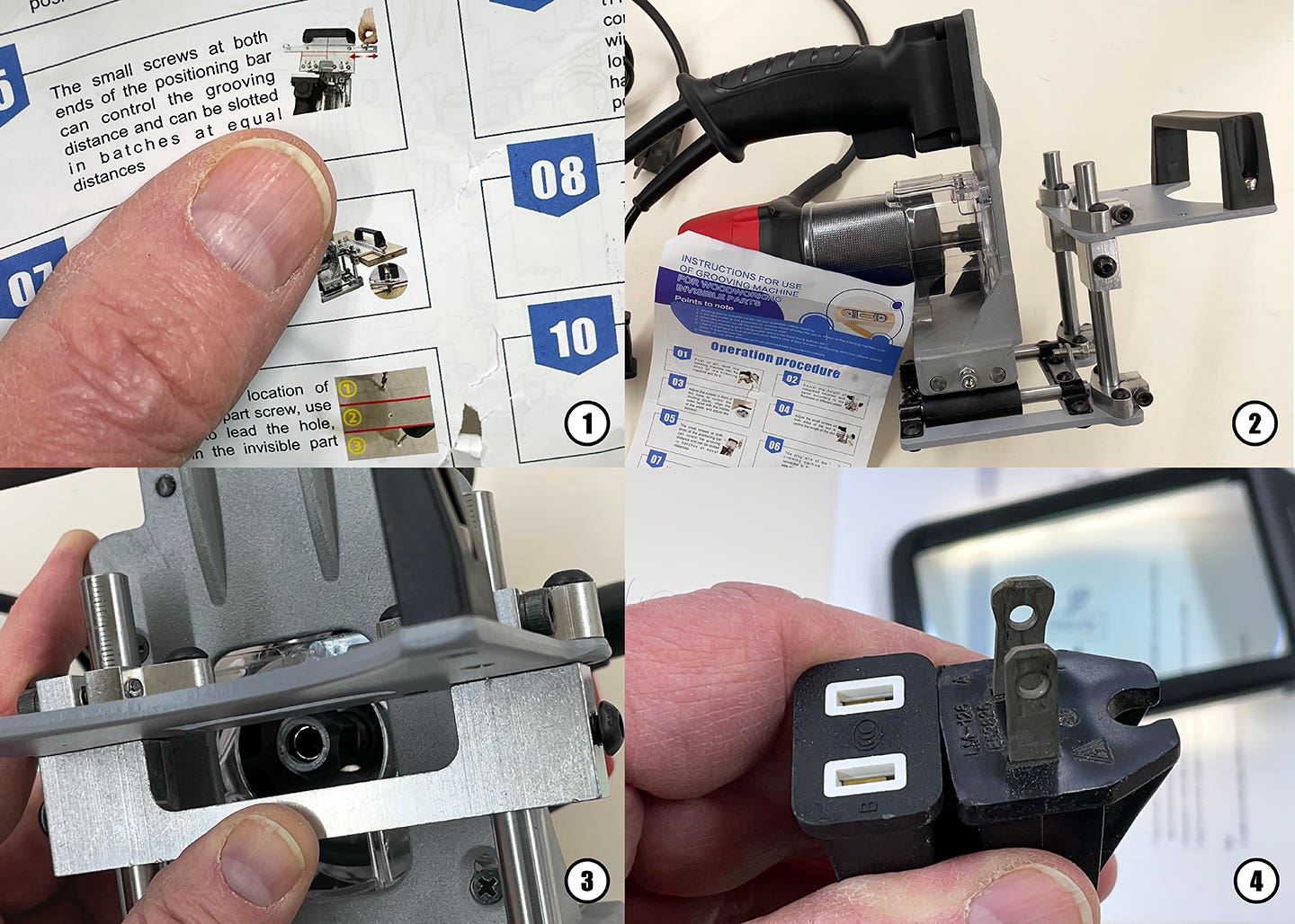

Before assembly you can cut rabbets on individual components with a dado set on your table saw as in the above photo. Or, you can cut rabbets after assembly with a router and a guided straight bit – often referred to, appropriately enough, as a rabbeting bit.

If you need more strength, there’s a variation called a lock rabbet that’s exceptionally adaptable to any carcase, box or drawer. It’s a bit more complicated – although not much – but a lot stronger if that’s what you need. More often than not, a regular rabbet will do fine.

Fast, easy and strong. If there’s a better qualification for a good method of joinery, I don’t know what it is.

A.J. Hamler is the former editor of Woodshop News and Woodcraft Magazine. He's currently a freelance woodworking writer/editor, which is another way of stating self-employed. When he's not writing or in the shop, he enjoys science fiction, gourmet cooking and Civil War reenacting, but not at the same time.