Are you listening?

Automation with AI and robotics is making a lot of noise in the woodworking industry

David Bowie once noted that “tomorrow belongs to those who can hear it coming”. Apparently, woodshop owners have good hearing. Casework and furniture manufacturers are undergoing a transition from traditional machines to automation, and hands-on labor to robotics. Prescient shop owners have accepted technology as a viable solution to the scarcity of affordable skilled employees, and that places them in the forefront of the new Industrial Revolution.

In the past, such revolutions meant more jobs. This is the first one to reverse that trend, which is a profound concept. Robots, and the artificial intelligence (AI) that is just beginning to drive them, are altering our workplaces and societal norms. AI is going to disturb the matrix of humanity more than automobiles, the Internet, cellphones or any other precedent technology. And while networking online gave us a means of sharing information, AI can both manufacture and distort the data that we share.

Cobots (robots that work safely around humans and avoid physical contact) are already widespread in woodworking. These machines are evolving rapidly as they tackle tasks that until recently were done by human hands. But soon AI will do the work of human brains, too. Well, somewhat.

The simplest definition of AI is that it allows a machine to both learn and deduce. But machine learning (ML) doesn’t let computers ‘think’ in the sense that we do. Our thought patterns are obviously influenced by facts, but they are also nuanced by emotional responses, belief systems, traditions, conventional mores, societal norms, and both individual and group experiences and dynamics. AI makes deductions based only on stored data. Some of its reasoning uses estimated values to jump gaps, but none of it depends on emotion or intuition. This limited intelligence is known as ‘narrow’ AI. The concept of an artificial intelligence that can actually think, using both reason and perception, is still in the future. That is called artificial general intelligence (AGI), and the technology to support it is in the pipeline but not yet viable.

AI in the woodshop

When narrow AI is used to track operations and monitor or control machines and processes, it does so by following sets of rules (algorithms) that were originally created by a human. Some AI operations can contribute to and alter the algorithms, creating a more effective and efficient path to garnering results. The algorithms learn by finding patterns in existing data. The more they see repetitive data, the greater their assumption of predictability. In other words, if every door that has passed through a CNC in a certain job gets an ogee edge, then the AI program assumes that all future doors need to be milled that way. But if 12 percent of the edge treatments are something else, then the program will assume there is only an 88 percent chance that the next door will conform, so it will need another variable to complete its deduction. That might be CAD input, or a manual change on the controller, or a barcoded label that gives it direction.

Providing instructions for the algorithm is known as supervised learning. But machines can also learn without supervision. They do that by sampling. For example, AI tools such as clustering or association might be used at a sawmill to grade and select hardwoods. The grading could be based on parameters including knots, grain patterns, color and defects. Clustering is a method of data mining that groups items with either similar or different characteristics (for example, knots of a specific diameter). Association simply finds relationships within the data.

Beyond supervised and unsupervised learning, AI also uses a technique called reinforcement to learn as it works. In this case, it constantly changes the parameters of its algorithms by basing its choices on success or failure, and it thereby learns to reduce or eliminate mistakes.

While all of this sounds a little like that old computer adage about “garbage in, garbage out”, there is a fundamental difference here. AI will accept the garbage in (poor algorithms or impaired data), but it can actually work on improving the output. It can help reduce human error or oversight by processing vast amounts of data and revealing patterns and probabilities.

So, supervised AI learning is where the operator ‘trains’ the program, while unsupervised and reinforcement learning are methods whereby the machine essentially trains itself.

AI is currently being used by larger woodshops in areas such as predictive maintenance, analyzing energy usage, tracking waste, optimizing, and managing just-in-time inventory. Indeed, proponents of AI are quick to point out the positive effects of artificial intelligence resource management as a means of lessening the industry’s impact on the global environment. More AI means less waste, and thus less pollution.

On a more intimate scale, AI is being used on the production line where generative algorithms can shave seconds off various tasks, and the cumulative effect can be significant time saving with fewer defects. An AI program finds small ways to speed things up, and over time or with many processes, this can have a significant impact on both schedules and budgets.

So, should a woodshop invest now in controls with advanced AI components? At this point, that largely depends on volume. The more production that is running through the plant, the greater the rewards from sampling and processing data. But for smaller shops, some AI will trickle down into controls and software, and eventually the technology will become as affordable as phones and tablets. AI is now about where pagers were before smart phones. There’s a lot more coming.

Cobots in the woodshop

As a musician, it’s easy to see why David Bowie would tell us to listen for the future. But another wise man, Abraham Lincoln, said that the best way to predict your future is to create it. That path is now open to even the smallest of woodshops, thanks to the cobots mentioned earlier. These collaborative robots are both affordable and adaptable, and they can transform a production line.

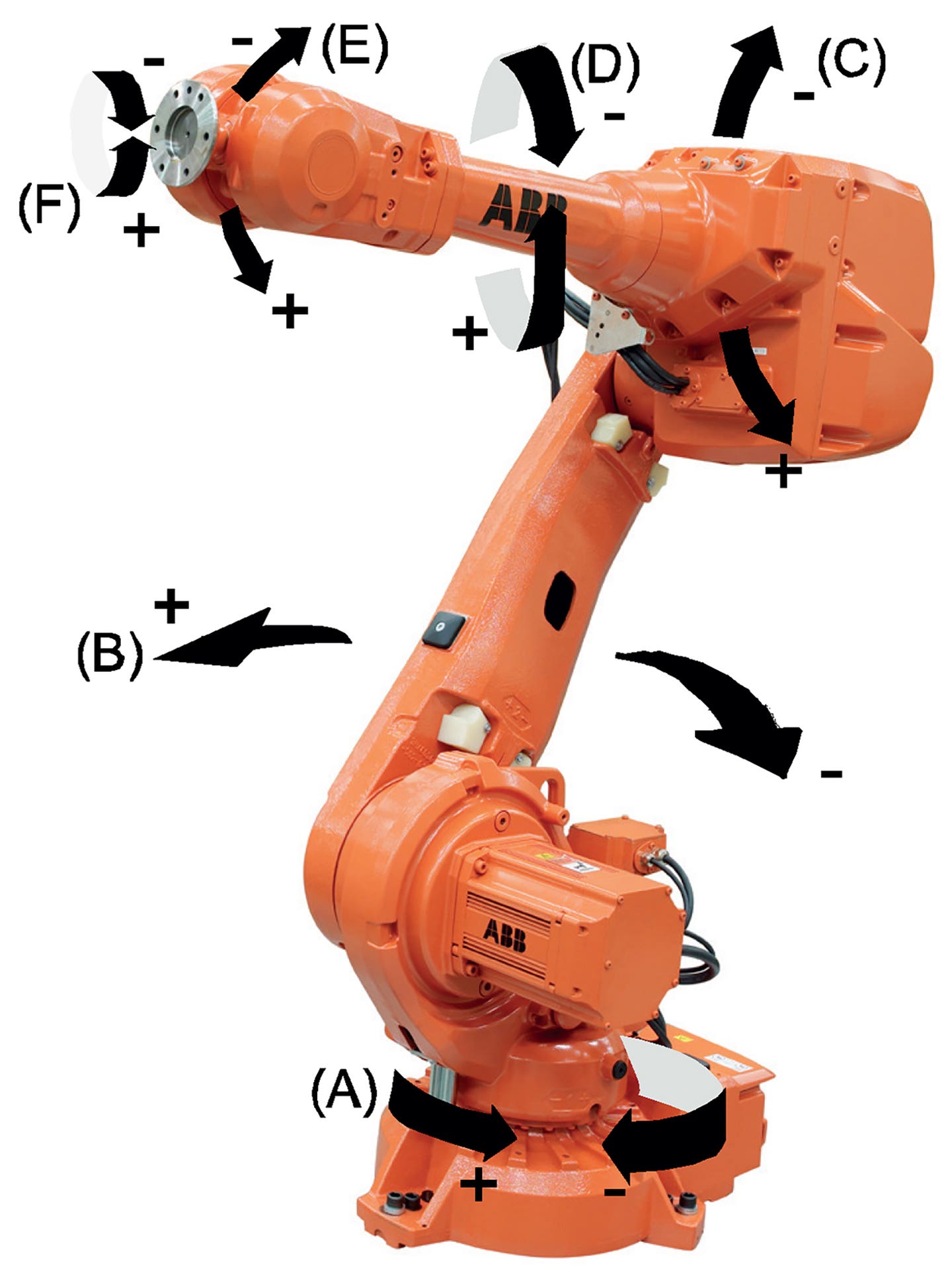

The main function of cobots is to automate the tasks that woodworkers find boring. These robotic arms are perfectly suited to repetitive work such as sanding, applying coatings, sorting and moving parts, and presenting parts to the tooling on machines. Many cobots are small and light enough for one or two people to move them from one workstation to the next. That makes them ideal for woodshops that produce small items such as advertising specialties, wooden souvenirs, hardwood handles and the like. In cabinet shops, cobots can be set up to perform tasks such as drilling for decorative hardware or panel connectors, gently breaking sharp edges, or perhaps milling edge profiles. One area they really excel in is sanding complex parts, especially when a small detail sander is attached to the arm.

Cobots are surprisingly easy to program. They benefit from having come into their own after smartphones and laptops, in a timeframe where technology has become very intuitive. Many run on simple apps with archeology that is already familiar to most of us. Indeed, many cobots can even be ‘trained’ by just moving them through the sequence of positions required by the task. They create a three-dimensional map as they move, and additional task instructions (stop here, rotate there) can be input later to build a more refined sequence of instructions.

Cobots shine in the spray booth. Their arm has extensive flexibility, and the ‘hand’ is far more versatile than a human one. It can swivel and rotate far beyond the range of wrists and fingers. Small shops are discovering that one cobot holding the part and another holding the spray gun is a magical combination. This pairing can dramatically reduce overspra, and address the nozzle at the perfect angle for complete and faster coverage on even the most complex parts or subassemblies.

Cobots are also working wonders with sanders. They can follow the curves of a chair seat or apply delicate pressure on thin veneers. They can be fitted with random orbit or inline sanders, and can learn to apply different levels of pressure, speed or repetition to produce a perfect surface.

Beyond consistency and ease of use, cobots also deliver recuperable cost. Most of the cobots being purchased by smaller woodshops cost less (and often a lot less) than an employee’s annual wages and benefits. So, they usually pay for themselves within months. And once amortized, they don’t usually cost a lot in maintenance. Cobots don’t take sick days or coffee breaks, or cause any workplace relationship problems, or quit without giving notice. On the other side of the coin, they don’t make creative suggestions or switch tasks instantly if needed, as a valuable employee can. But if a shop can’t hire people, then cobots are a solid substitute.

Practical applications

In May 2024, Fanuc America (fanucamerica.com) introduced a cobot designed for industrial painting, coating and powder applications. The new CRX-10iA/L Paint works with high-mix, low-volume applications, but also is designed to comply with the most stringent explosion-proof safety standards in the U.S. Woodworkers with no robotics experience can deploy the new cobots to automate painting and coating processes by using “easy-teach” features. The new cobot will be available in September.

Indiana-based Robotic Solutions (roboticsolutionsinc.com) is the exclusive importer of CMA Spray Robotics (cmarobot.it), an Italian company that has been working on the evolution of self-learning. It has also created a lead through teach option where, instead of sitting at a computer and programing the robot, a woodworker uses a joystick with a spray gun to coat the first wooden part while virtual reality tracks the process. The resulting program can be edited using a CMA offline programming tool to perfect the paths, after which the robot arm can take over and spray the rest of the job by mimicking the human’s movements.

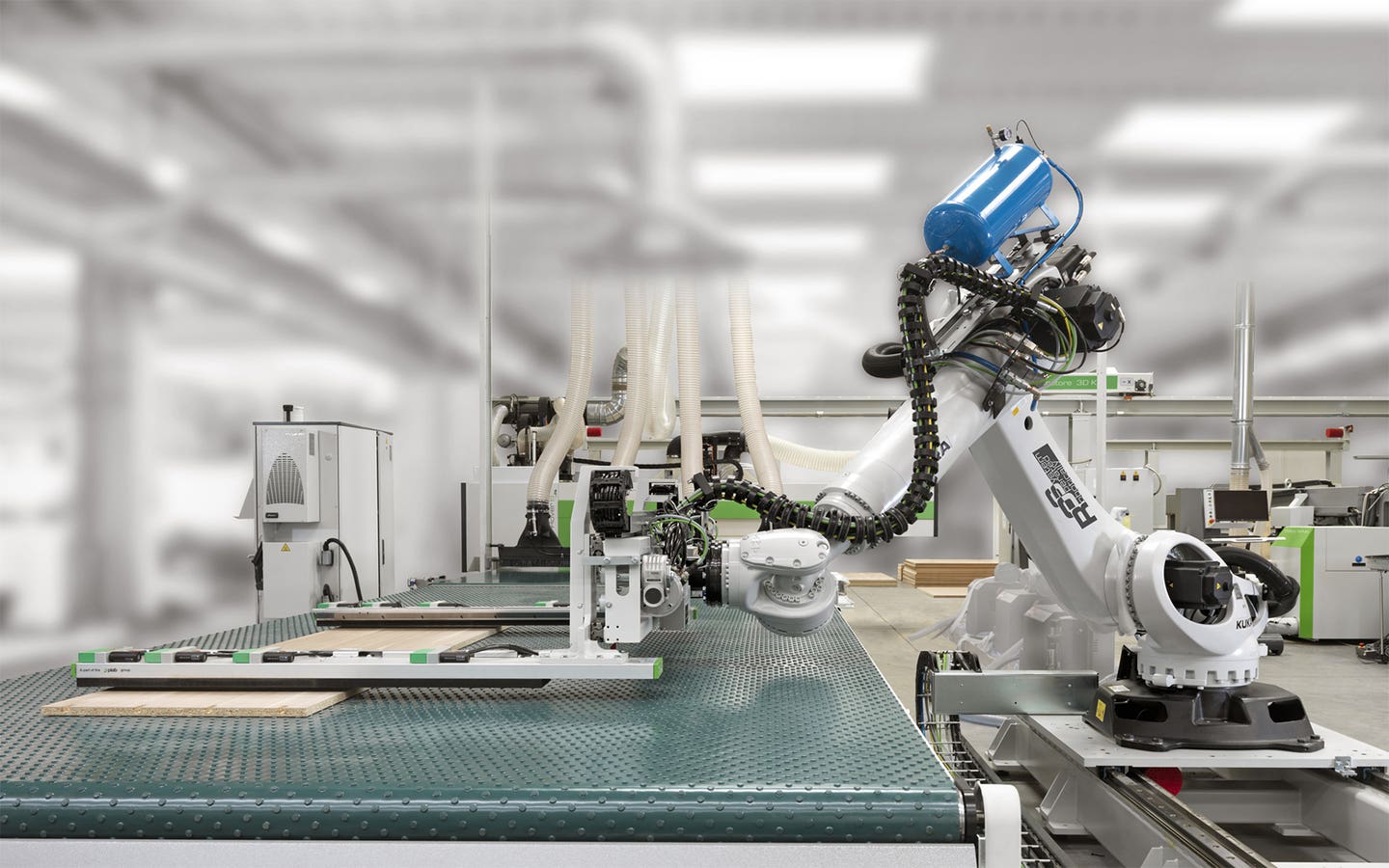

Robotics Solutions also imports robots from Kuka (kuka.com), which introduced a new large cobot, the KR Fortec, earlier this year. Its arm can lift loads up to 240 kg (529 lbs.) and has a reach of 700mm (27-1/2”). Considerably lighter than its predecessor, it was designed to achieve a lower total cost of ownership. Among the attributes that aim to achieve this is modularization, which means that parts are interchangeable between models. That translates into lower costs for spare part storage. The KR Fortec has two waterproof and (more importantly) dustproof wrists. Plus, its workspace can be expanded using a track system called the LK4000, which can be anywhere from 1.5 to 30 meters long.

Last November, the Danish cobot manufacturer Universal Robots (universal-robots.com) announced that it will expand its product portfolio with a new 30 kg (66 lbs.) payload cobot. Universal, which has a significant North American presence, says that “despite its compact size, the new UR30 offers extraordinary lift, and its superior motion control ensures the perfect placement of large payloads, allowing it to work at higher speeds and lift heavier loads.” (For reference, a sheet of 1/2” ply is about 50 lbs.) Universal suggests that the UR30 is well suited to tasks such as machine tending, material handling and high torque screw driving.

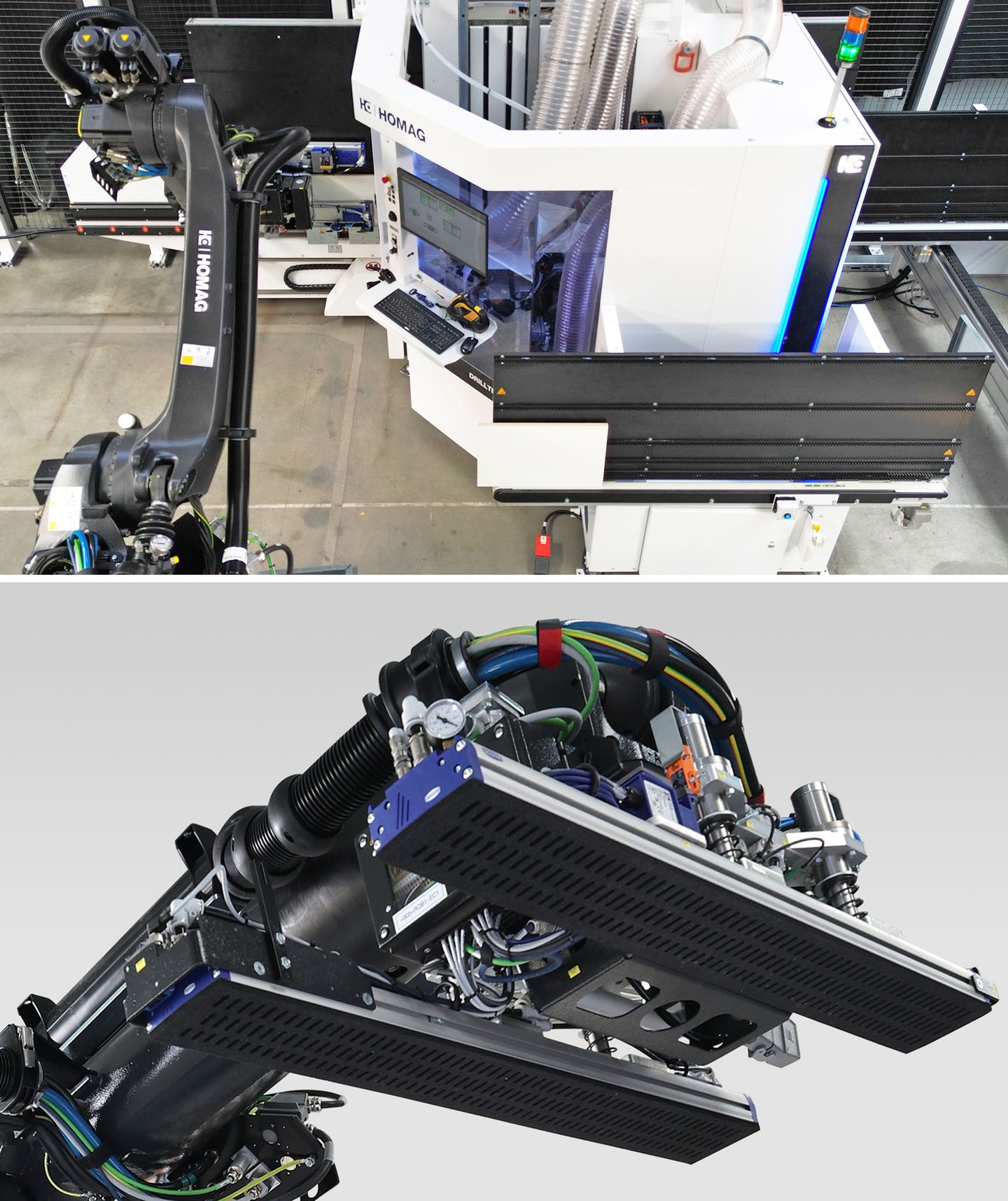

Among the newest additions from Homag (homag.com) is the Feedbot D-310. Designed to reduce the overall cell size of workstations, it allows for processing on both sides due to a return conveyor reversing function. It can handle loads up to 60 kg. and workpieces up to 3050 x 1250 x 80mm (120” x 49” x 3.15”).

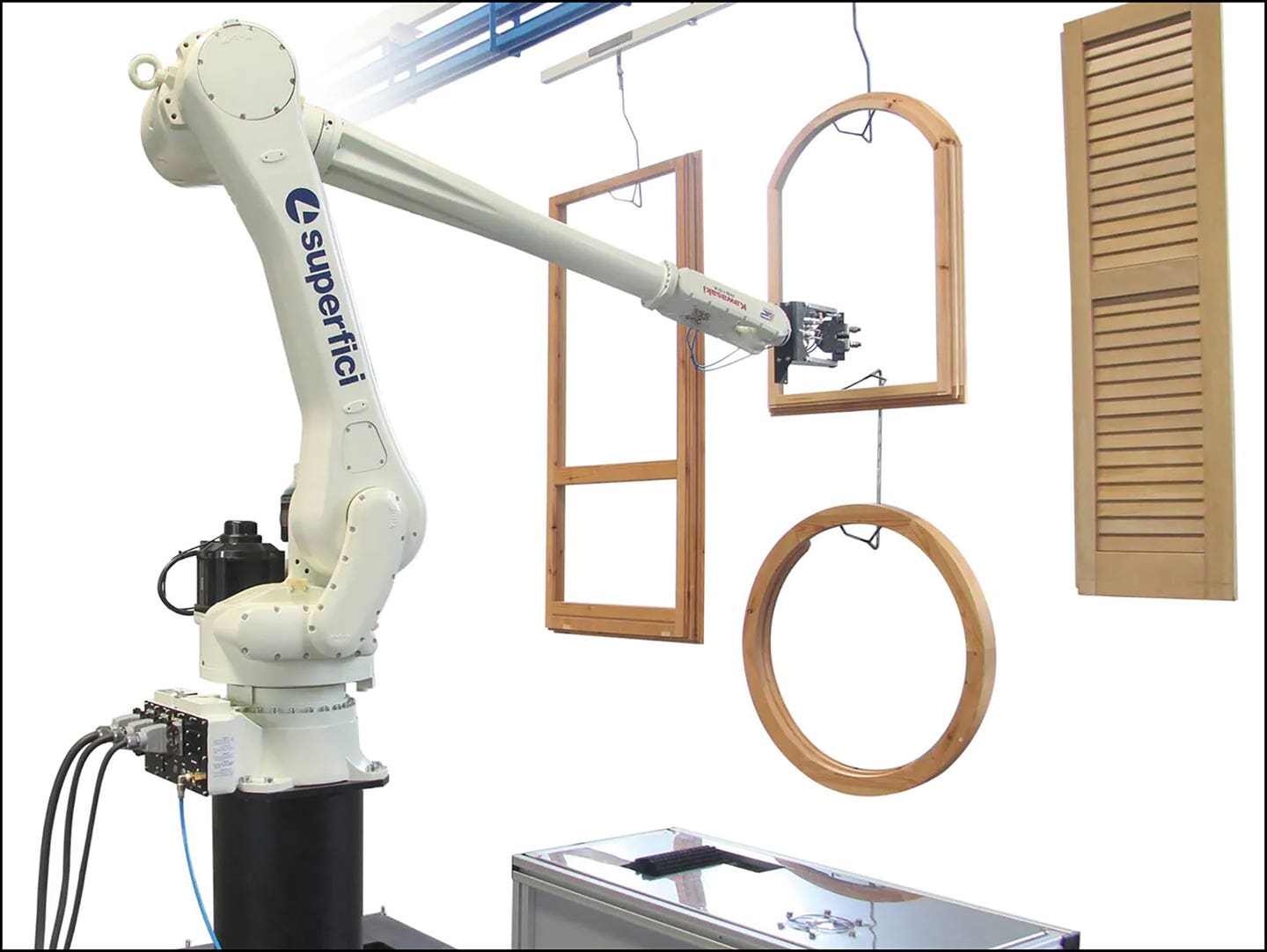

The Robot Maestro from SCM Group (scmgroup.com) is a 6-axis anthropomorphic robot with the possibility of an extension to 11 axes. It’s ideal for coating items such as window frames and doors. It’s equipped with a gun holder tool (seventh axis) and supplied with a brushless motor that allows it to spray all parts of the product. The Maestro can manage spray angles from 0 to 90 degrees and its exhaust recovery system and brush nozzle cleaning can be set by the software.

The Biesse Group (biesse.com) says that its Robotically Operated System (ROS) is “ideal for rail boring-insertion lines and can be seamlessly integrated with a CNC for the machining of doors with waste and strip management.”

Vention (vention.io) has developed a system that can automate a woodshop in a matter of days. The company’s cloud robotics platform is designed to simplify the design, automation, deployment, and operation of robot cells. The available modules include tasks such as sanding, machine tending and palletizing. Vention offers a comprehensive library of modular components with plug-and-play compatibility. Recognizing that no two shops are identical, the system slots various tasks into the line so that a shop’s manufacturing process can be intimately customized.

The unusually named 7robotics (7robotics.com) is an Oregon-based supplier of robotic and automated systems in the wood products industry. The company can design digital twins and 3D models to help its customers better visualize the production process. A digital twin is a computer graphic that accurately reflects the dimensions, shapes and movement of a physical object. So, the designers can build a virtual robotics system for a woodshop on a computer, and that can then become a physical system after the kinks are all worked out.

AutomatechRobotik is a robotics supplier in Quebec that has been working with the wood industry since 1977. In the U.S., it partners with Stiles, Kuka and Biesse to design solutions for woodshops. The company’s website (automatechrobotik.com) includes a very interesting essay on what is possible today, and what is still science fiction. It’s well worth a read for anyone who is contemplating the use of available technology to create a fully interconnected production line. The article describes how parts can be tracked with RFID tags and manipulated by robotics, while everything can be orchestrated and analyzed and optimized by MES and ERP systems.

Located in Pennsylvania, Ideal Machine (idealmanufacturingllc.com) is a wood processing machine manufacturer that builds products such as a high-efficiency stile-and-rail shaping system, and a double pocket hole machine with automatic screw insertions. That hands-on background has led it into supplying robotics for tasks such as sanding and tending (loading and unloading CNCs) that are specifically designed for custom shops. The company points out that using robots for tasks that workers find boring means that the more important and interesting jobs can still be done by humans without sacrificing quality or volume. Ideal Machine has partnered with Ehst Systems and Controls to form Penn Lancaster Robotics, which supplies small- to medium-sized shops with everything from design services to robot learning and programming, and operator training.

Some other innovative names in this field include Kawasaki, Ferrobotics, Doosan and Lesta, but the field is expanding rapidly. Visiting a trade show such as IWF Atlanta this August is perhaps the best way to learn about the latest options. What we’re going to see over the next few years is an increasingly productive marriage of robotics and AI in the woodshop. As the machines continue to learn and perform more tasks, small woodshop owners may surprise themselves by bringing back some outsourced tasks that they can now automate. And shop owners may also find themselves becoming more creative as their machines begin to think.

Tomorrow belongs to those who can hear it coming. David Bowie heard a very distinct future that included hits such as Starman, Space Oddity and Life on Mars. His vision is rapidly coming into focus with the privatization of space flight and a thermosphere crammed with satellites.

Back here on Earth, cobots and AI are equally revolutionary. But there’s no need to listen because they’re not coming. They’re already here.

Originally published in the July 2024 issue of Woodshop News.