Is it time to automate?

Growing shops might want to consider machines and robots for finishing. Finishing takes time, and finding ways to fully or partially automate without breaking the budget can be challenging.

Finishing takes time, and finding ways to fully or partially automate without breaking the budget can be challenging.

Smaller woodshops that do their coating in-house usually use a manual system where an employee wheels parts into the booth, sprays them, and then wheels them out to racks, or maybe a dryer. The next step up from that is to have a hanging line that travels through the booth, so the operator stands in one spot and the parts can be moved and rotated as needed. After that, there’s machinery such as the flat line finisher, which runs parts through a CNC spray booth where the operator feeds them in and collects them afterwards, but never touches a gun. And at the top of the food chain is the fully automated robot.

The most cost-effective method for a woodshop is going to depend on volume and frequency – how many parts need coating and how often – plus the shape and size of those parts. So, let’s take a look at some equipment options.

Manual spraying

The huge advantage here is the low setup cost, but that’s a little deceptive because like buying an office printer, the equipment is cheap and the liquid is expensive.

A manual gun, operated by an experienced employee, will still only deliver a small fraction of the liquid coating to the part, so waste levels are high. And the challenge isn’t just overspray, but also unequal spray. As a human arm swings in an arch, more material is sprayed the closer the gun gets to the part. That can cause runs and reworking. Overlap is eccentric, too, as a pass could cover 50 percent of a previous pass. While HVLP equipment will certainly cut down on overspray, a person holding a gun at arm’s length will always be operating with more art than craft.

Manual spraying equipment for small shops usually involves an inexpensive open-face booth, a small portable booth, or sometimes just a fan in the window. It can use a lot of shop air to make up for the contaminated air that gets exhausted, and that can be spendy if the make-up air needs to be heated or cooled depending on the weather. A fully enclosed booth with filtered doors is a step up, and while most of those also need make-up air, both the incoming and outgoing air is scrubbed so contamination is minimal.

All that is needed for manual spraying is a gun, a pump, a mask, and venting. Done right, it can be a very economical solution for occasional spraying. A dedicated parts hanger can really speed up the process, where panels are suspended from a rail and can be accessed from all sides, and then are slid along the rail and left to dry. With cabinet doors, these systems usually take advantage of the drilled recesses for 35mm hinges to hold the part in place, so the operator gains access to both faces and all edges without having to touch the door. And if the rack has wheels, the shop can move, spray, dry and store parts hands-free.

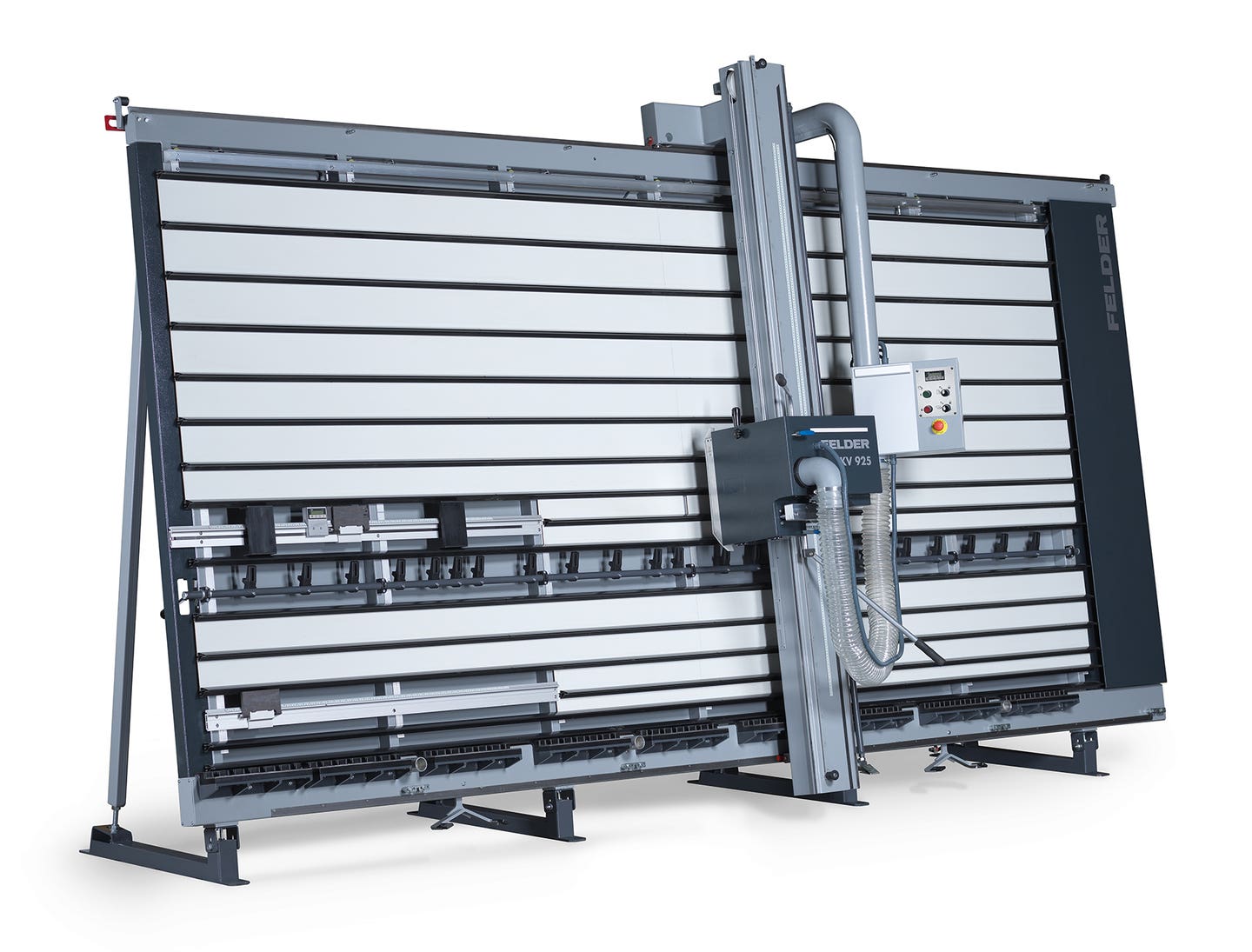

Finishing machines

Moving parts through the booth rather than moving the operator is a logical next step. There are lineal finishing machines that can handle profiles, moldings, trim, and other thin stock. And there are flat line machines that are designed to coat flat panels, doors and drawer fronts.

Most of the flat units are a few inches wider than an MDF sheet, so even a full sheet can be sprayed and still get the edges coated properly. For cabinet doors and other parts, the machines have sensors that see and note the dimensions of each part, so they can program the spray gun(s) to turn on and off in the most efficient sequence. The airborne overspray is filtered and then exhausted outside. These machines don’t get tired, so the result is more consistent than a real person spraying a large job.

Flat line finishers feed the parts through slowly (usually about 10 feet per minute). To do that, they have either a paper or a self-cleaning belt that works a lot like the conveyor in a wide belt sander. The paper version is a huge roll on a wheeled cart that’s lined up at the front end, and the leading edge of the paper is fed through the machine. The parts are laid on the paper, which catches the overspray. As they exit the machine, the paper beneath them is collected on a take-up roller and then discarded. This is usually brown kraft paper and it comes in rolls that are 8,000 feet or more in length. The big advantage to paper belts is that they are easy to clean up (no solvent) and most landfills will accept them when dry. The biggest disadvantage is that the used rolls take up about three times the space of a tightly wound new roll. They also take a little time to set up and remove, and the shop will need a small forklift to move them.

The self-cleaning belt is usually associated with higher volumes and it allows the shop to possibly reclaim some non-catalyzed coatings. The machine scrapes liquid overspray off the belt and gathers it in a reservoir, where it then flows into a bucket. The saved fluid can then be strained and re-used, and with most of the overspray removed the machine can use solvent baths to clean the rest before the next batch of doors is popped in place. The downside of a self-cleaning belt is that it uses that solvent, which can be expensive and must be responsibly disposed of. The belts will eventually wear down, too, but that can take years.

If a flat line finisher sounds interesting, the next step is to look at one or two arm machines. The one-arm is for slower runs. The arrangement is usually one arm with one, two or four guns being run by one compressed air pump or ‘paint circuit’, or else two or four guns on each of two arms. The parts are placed at least twice their thickness apart, so the edges can be sprayed. As the guns move from one side of the chamber to the other and back (each return trip is called an oscillation), the parts being sprayed are constantly moving under them. Both the belt and the oscillation speed can be adjusted.

Flat line finishers can be pressurized or non-pressurized. The latter is open to the shop or booth air, while the former uses filtered pressurized air to direct and control spray patterns. The air is also filtered as it is returned to the environment after use.

Robots

Robotic painting solutions are a possibility for many shops with higher volume. The robotic arms can be mounted anywhere inside the booth, but will often require some extra structure to support their weight and movement. Floor-mounted tall robots are the easiest to install. Loading can be manual or automated. One of the more common configurations is hanging doors from a conveyor or overhead rail that moves them into position, revolves them as needed, and then moves them out of the booth. Some robotic booths take advantage of the fact that robots don’t have lungs and they recirculate the air (and any VOCs) without having to exhaust constantly. That can save quite a bit on heating or cooling make-up air.

The accuracy and speed of robotic arms also help to cut costs. There are very few rejects or reworked parts, and cobot or robot arms can move a lot faster than a human. A good rule of thumb is that adding a painting robot will cost about the same as hiring one human for a year.

This article was originally published in the September 2023 issue.