Automating the finishing department

The market for spray machines and robotic applicators has exploded with an array of choices

For many smaller shops, finishing is still a manual task that's done with a brush, rag, roller or spray gun. But that could soon change as entry-level automation becomes more affordable.

Automated spray machines are designed to be stationary units in a production line. They work like wide belt sanders – the woodworker feeds parts in at one end and a mechanical conveyor moves them through the machine until they emerge, dry and handleable, at the other end. The machine is basically a big box with air filters that recover or remove overspray, a spray gun, and a large sheet of paper or a cleanable belt that keeps the parts moving. Sometimes the configuration is two machines in series, where one applies the coating and the next does the curing. The paper belt is discarded after each job, or the cleanable belts are either automatically or manually cleaned as needed.

The advantages of automated spray machines are that the coating depth can be extremely even, errors are rare, and overspray is very well managed. They're also faster than manual work, so they release employees to do other tasks. They can be programmed to spray just about any liquid coating, and the spray pattern, nozzle distance and fluid volume can all be programmed to change as needed during the process. One of the biggest selling points of these machines is that the learning curve is quite short, as they are fairly easy to operate.

A woodshop can choose between many machines, depending on what is being coated. When shopping for a machine, the width and height are critical while most machines have open ends for long stock. The number to watch for is feet per minute, as this tells you how fast a job can be processed. Choosing the feed speed is determined by the viscosity of the liquid, its evaporative qualities, the depth of the finish, and the size of the parts. The machines have a comprehensive control panel that can usually be programmed for manual or automatic input, so each job can be handled differently as needed.

Long and thin stock such as moldings, stiles, rails, siding and trim are best served by a fan coating head or a linear spray machine. The fan coater is exactly that – a fan shaped spray head that delivers a wide and thin mist. Most machines will have several fans, and they usually have more than one filter so the operator can clean up without stopping the machine.

Other setups

A linear spray coater has an overhead gun or guns, a long conveyor belt, and guides that usually include a hold-down roller before the guns. They're simpler machines that are easy to maintain and clean. Bigger machines can handle hundreds of feet per minute but their limit is part width, so some wide architectural crowns or large historical reproduction base moldings won't fit on smaller machines. High volume (more expensive) linear machines can have multiple pump circuits and multiple gun arms.

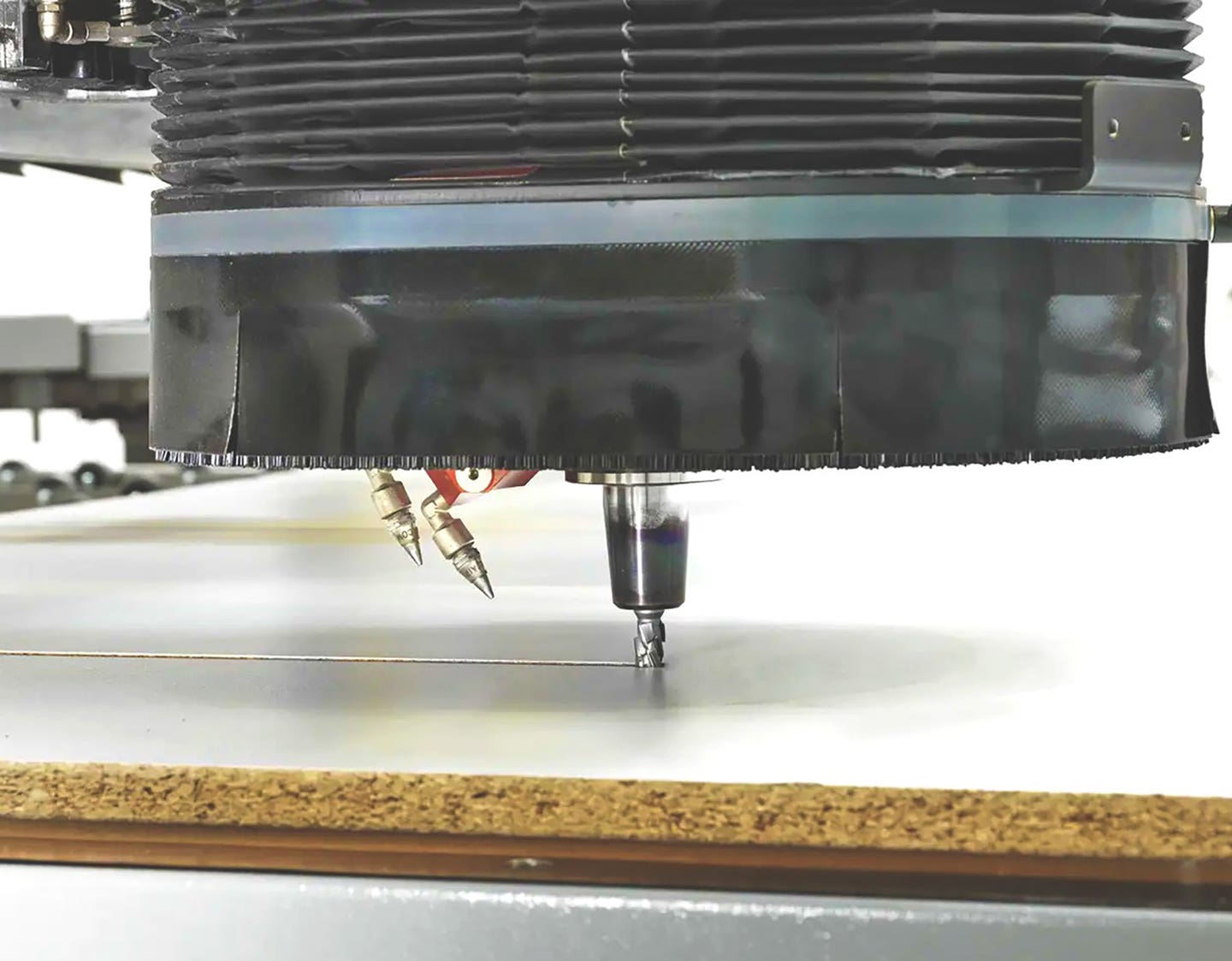

A reciprocating head is a solid choice for kitchen elements such as five-part doors, drawer faces, shelves and flat panels. Basically, reciprocating means 'moving'. The machines have sensors that tell them when a part is entering the chamber and the size of that part. The working head's action is very familiarto CNC owners. It can be equipped with one, two, four or more guns, and it moves quickly in X and Y. It can also angle/rotate as needed, to coat edges. Most machines now have LED lights and inspection windows so the operator can watch what's happening in real time. For cabinet doors, the normal process is to coat the backs, and then do a second run to coat the fronts. One thing to keep in mind is that spray coating machines use extraction fans and filtered air intake/makeup blowers, so there will need to be some infrastructure (and budget) for those.

Most reciprocating machines have easy gun switching, which lets the operator change coating material or colors without having to go through a full clean-up.

Larger doors, complex surfaces and cabinet components are usually coated using rotary spray machines. Here, the parts move under heads that rotate on arms as needed. They can spray a fine, even mist over a wide area, and they move parts through a lot faster than reciprocating machines. Sensors or scanners tell the controller where to concentrate and where to be circumspect on complex parts, so even sculptural components can be evenly coated. The volume of delivery is controlled with a combination of variations in the line (feed) speed, and the rate at which the arms rotate.

Spray coating machines come in airless, high pressure, medium pressure and HVLP options. Some are set up for powder coating, with dedicated recovery that pretty much eliminates waste.

Robots and cobots

For smaller shops, robotic spraying can be a very custom, one-part-at-a-time process and this can be a significantly smaller investment than a tunnel machine. Here, small robots can pick up one door at a time and hold onto it using clamps that fit into the 35mm hinge mortises in the door. While one arm secures and moves the part, another moves the gun. Simpler entry-level systems are also available where only a gun arm is used. And there are spraying and drying systems that hold doors, drawers and even case goods in other ways as they present them to the spray gun, and then move them through the spray booth for airflow or heat based drying/curing.

A cobot is a collaborative robot, which is basically a mechanical arm that has sensors on board that can detect people and other objects, so it doesn't bump into them as it moves. Cobots are made up of a base, a flexible arm with full rotation in the elbows (so it can move a whole lot more than a human with a spray gun), a flexible wrist, and a controlled tool at the end of the arm. Cobot arms can move a spray nozzle parallel to a part, rather than using the swaying arc that nature imparts to human arms. As a result, robotic spraying equipment is very precise and uniform, and consequently wastes very little of the liquid. These arms can also be set up to repeat processes, so similar doors in subsequent jobs can be coated with less set-up required. That recipe approach reduces errors, and waste.

Small cobots are essentially batch machines. That is, they are intuitively best suited to batch processing rather than continuous process. They start and stop smaller jobs, rather than running large volumes all day. Some cobots have more or fewer axes than others (it's usually about six) and the more they have, the more complex parts they can reach.

Many robotic spray systems now use basic AI to teach the cobot how to spray. The operator holds a gun and physically goes through the movements, and the arm 'learns' from that. This is a way for users to avoid excessive programing. They can teach the tool, performing operations in short phases that can then be sequenced to create complete tasks. The trade term is mimic software.

Two critical aspects to ask about when exploring the cobot option are the arm's reach (how far can it be cantilevered from its base without losing precision), and payload strength (what weight can it handle – and that includes guns, hoses, and liquid). For complete coating systems, the equipment may include the option of color changers and purging equipment, different delivery and pumping set-ups (pneumatic, electrical, piston, diaphragm and so on), and various ways to handle, mix, recover and store fluids. For example, some manufacturers offer dosing units that mix colors, thinners etc., while others require the shop to do all the prep.

Cobots are low maintenance. Once one of them is programed and the product is fed to it, it will just get on with the job without continuous tweaking or monitoring. And they don't require specific orientation. They can be attached to a bench, cart, floor, wall or ceiling – wherever they can achieve the best coverage.

Cobots don't breathe, so they don't have the same health and environmental concerns as human operatives. They also don'ttake up a lot of shop space. As a way to automate finishing equipment, they can pay for themselves very quickly when their price is balanced against the cost of training and employing a paint booth operator.

Whether a woodshop is searching for finishing tunnels or cobot arms, the bottom line for any kind of production run is automation. Choosing the level, and the investment size, is a complex journey but it can significantly reduce finishing costs over more traditional methods.

Originally published in the October 2024 issue of Woodshop News.