It's a harsh reality for woodworkers when they realize that their brand-new CNC router has quietly become several years old. Time slips by and machines, like their operators, start feeling dated.

But unlike woodworkers, the physical depreciation of a CNC doesn't automatically consign it to retirement. As long as the heart is strong, there are lots of ways to give it a whole new lease on life.

Retrofitting

For a CNC that still has a solid frame, flat table and trouble-free gantry, replacing the control panel may seem like a sensible upgrade. But faster controls will probably dictate upgrading the servo motors too, along with the spindle, most of the wiring, the capacity of the tool changer, and swopping out a few ancillary electrical components. A full retrofit can cost a pretty penny, but it's still far less expensive than buying a whole new machine. That's especially true when the shop has already paid for the infrastructure to support the CNC including the power supply, dust extraction, loading and unloading mechanics, clamps, fixturing, vacuums and all kinds of jigs and adaptations.

Leaving the machine where it is can minimize downtime, too. The true cost of selling an old CNC and buying a new one involves a lot more than just the price tags. There will be days, even weeks, during the transition where nothing is built. Then there's the huge cost of shipping a large chunk of iron (two, as the old machine must be moved, too), and hidden costs such as interest rates and time spent training on the new machine. These other numbers are what convince many woodshops to retrofit rather than replace.

There's also value in the operator's comfort with the existing machine, with its physical space in the shop, and its unique idiosyncrasies. Of course, some of those norms will change with a faster controller, a more powerful spindle, and a larger toolchanger. But the heart of the machine is familiar, intimate and understood. That inspires a degree of confidence. So, even though the retrofitted CNC is almost an entirely new entity, its core familiarity imparts a sense of ease rather than the trepidation that often accompanies learning about a new piece of equipment.

The latest generation of controls can compensate for slight irregularities in an existing machine, so cutting results are often more precise after a retrofit. Processing is also going to be faster, and maybe a lot faster if the spindle is also upgraded.

The retrofit can be done at the woodshop, so there's no need for forklifts, cranes, or moving other machines. And there's no need to disconnect power, compressed air, vacuum and dust collection lines to gain access. Plus, all the new features will be under warranty for a while, which helps ease one's mind during the transition.

The usual process is that the woodshop contacts the retrofitter who sends a tech person or a team out to evaluate the existing machine and make recommendations for upgrades. Once a path forward has been decided upon, the service company will build a new controller and probably a whole new electronics cabinet, too. That, along with other hardware upgrades, is then shipped to the shop, and a crew of technicians soon follows to install and update the software. Some service companies will do the work at night or over a weekend, and they may even run new wires while the machine is still operating on the old ones, to minimize downtime.

Once everything is installed, the CNC gets tested and calibrated, and that can shut down production for a day or two. Then the woodshop employees are trained in the new controls and maintenance schedule, after which they can get back to work on client projects.

Full retrofitting is generally done to larger, more expensive machines. That's because there's a point where it will probably make more sense to buy a new CNC rather than rebuild an entry-level model. But the service company will provide an estimate based on make, model and year, so it quickly becomes obvious if the numbers aren't going to work.

Popular upgrades

Woodshop owners who already have a 3-axis machine sometimes think of 4- and 5-axis CNCs as being the next natural upgrade. Adding a fourth axis isn't for everyone, but it's a logical upgrade for shops that want to make round parts for architectural elements and furniture. A fourth axis lets the CNC do turning, so now the shop can make balusters, newel and porch posts, finials, pilasters, table legs, chair stretchers – in fact, anything that can be turned at speed on a traditional wood lathe, including bowls and even some hollow vessels. Or when it's turning slowly, a fourth axis can allow the shop to execute gentle curves, swirls, ropes and other decorative elements that can't easily be made with three axes.

If, on the other hand, the woodshop makes rectangular and flat casework, doors, drawers and the like, a fourth or fifth axis probably won't revolutionize production as much as doing a retrofit to increase speed and accuracy. Or upgrading a major element such as a vacuum table, tool changer or aggregate head may be wiser than adding a C axis.

Custom enclosures are one of the more popular upgrades for CNCs. They're relatively affordable and they provide a clean environment that reduces rework and maintenance. Some enclosures have a ceiling that is a filter system, while others side vent. Once an enclosure is in place, the limited volume of air now trapped around the machine can be cooled or heated without having to pay excessive utility bills for climate control throughout the whole shop. That limited enclosed space can also be kept relatively dust free, so parts can be manufactured in a space with low contamination and regulated moisture content. Enclosures can limit the transfer of airborne fines that travel between the shop's traditional machines and the CNC. They can also reduce harmful sound levels, and both of those factors (reduced dust and noise) increase operator safety.

The ability to regulate humidity is also a reason that enclosures are becoming more popular in geographical areas with extreme seasonal temperature variations. This helps with rust issues on machine beds and bolts, and reduces moisture absorption by the wood so there's less movement and lighter weight.

An inexpensive upgrade for shops with a vacuum table, even a small one, is a set of gasket tiles that let the operator block off unpopulated space and increase the holding strength of the vacuum. Some gaskets still have small hole patterns, so they don't completely block airflow, and that makes it a little easier on the pump.

Marking, barcoding, stickers, stamps and scanning devices can be an inexpensive upgrade. These help the operator keep track of parts and orient them properly during assembly. The machine manufacturer may recommend (or supply) compatible marking devices and software for specific CNC models, but there are a wide range of aftermarket options online.

Load, align, sweep

Loading full sheets onto a CNC and then unloading the cut parts can be a labor intensive and time-consuming task. For small shops, a conveyor/roller table on wheels is a huge upgrade and these are very affordable. Two tables are even better: one for loading and the other for offloading. Some tables expand and contract for a perfect fit in confined spaces. Most have adjustable legs so they can be set up at the same height as the CNC bed, and others can be manually raised with a pedal as the stack of sheets diminishes.

Manufacturers of 4x8 or larger CNCs can either supply or recommend automatic loading and unloading devices that are compatible with their machines. Some attach to the gantry and have bars with vacuum heads that grab and pull a sheet into position (it's usually a two-step process). Then the attachment moves the sheet so that one end and one edge are butted up against location pins. Aftermarket sheet loaders are hard to find online, so the CNC manufacturer or a user group may be the best resource for finding one.

Others sheet feeders are free-standing stationary machines, and there are some manually operated vacuum lifts on wheels that will lift a sheet, let the operator wheel it into position, and then place it gently on the table.

With advances in AI, robots are becoming the standard way to tend machines and feed sheet goods. They have become more affordable and more widely available over the years, even for small shops. Robotic arms can pick up a sheet, place it very precisely on the workspace, and hold it in position until the fixturing or vacuum engages. They can also pick up and sort parts according to size, orientation or label, turn them over and stack them for edge banding, and then sweep and vacuum the table before the next sheet is placed. That latter process is a lot healthier and more productive than an operator using compressed air to blow the table clean.

Robots that can lift full sheets are pretty sizeable. They need to have the payload capacity and the reach to do the job, and both of those abilities come at a price. A 4x8 sheet of melamine-coated MDF runs close to 100 lbs., and it will need to be moved at least four feet and possibly more. So, some set-ups use more than one robotic arm, and that can up the price, too. Others move sheets in stages, dropping them and repositioning as needed.

A woodshop owner can add up all the time spent manually loading and aligning sheet stock, and then unloading cut parts and waste over the course of a year. When one balances those man/hour costs against the price and operating cost of a robot, the numbers start making sense.

Panel alignment is another basic upgrade that can quickly pay for itself. If the shop can't justify the cost of robots, then adding pop-up pins that are automatically controlled with pneumatics or electronics, or even manually with a foot-operated switch, can speed up alignment after loading.

Aggregates

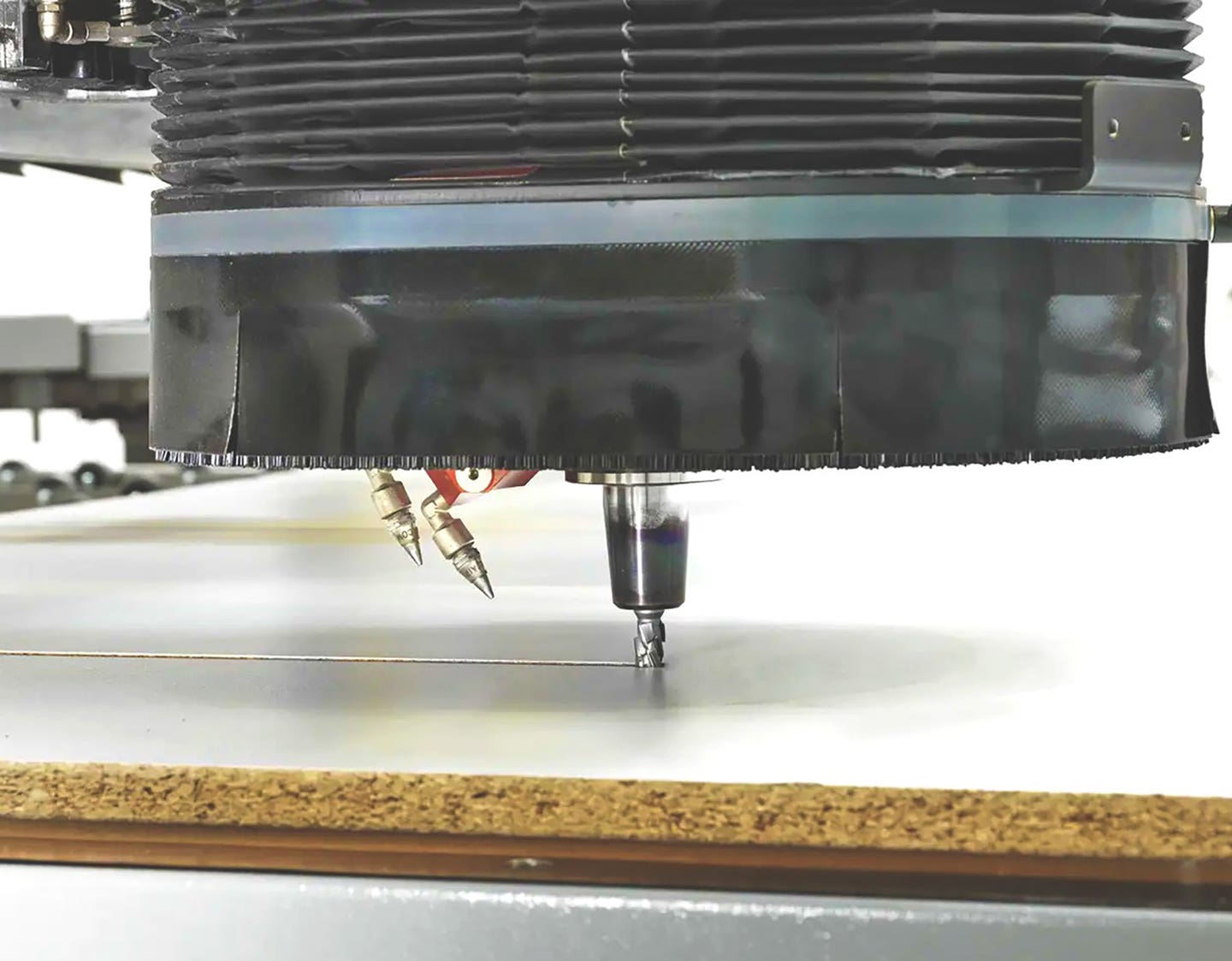

A standard CNC router has a spindle that points at the floor. An aggregate lets that spindle point a tool in any direction from down to sideways (90 degrees), which means it can work on the sides and edges of parts. But it also expands the number of tools available. A quick online visit to an aggregate supplier lets the owner of a 3-axis CNC discover a whole new world of possibilities.

There are a couple of caveats, such as the fact that an aggregate places the tool farther away from the spindle. That means there can be a reduction in power, a bigger possibility of heat build-up, and a loss of accuracy when the tool travels sideways and shear pressure engages. But for small parts and short runs, aggregates can revolutionize what a CNC can do.

Aggregate heads are usually offered in either grease-lubricated, maintenance-free models for short run work, or heavy-duty units with oil bath lubrication for production runs and deep cuts.

Tooling for aggregates includes the familiar drills and router bits, but there are units available that can handle wire brushes, circular saw blades, long and short bits, and more than one tool at a time. They can plunge, notch, chop pockets, work on the underside of parts along the edges, or do molding and shaping at any angle from 0 to 90 degrees. They can ease edges or chamfer, round over, flush trim, and even float so that the bottom of a groove is consistent even when the top surface undulates. There are aggregates for nesting, parallel drilling, pocketing and slotting, and even for drilling connected holes for hardware such as Lamello’s Cabineo.

A woodworker can attach a sanding aggregate that uses inline or orbital action, and there are belt sanding aggregates that can clean up edges in a jiffy. Chisel units will chop mortises for tenons, and knife units can slice through cork, leather, felt and similar materials to make items such as drawer liners, or protectors for lamp bases. There's even a chain saw aggregate for making larger, deeper mortise pockets for heavier furniture joinery, and a blower unit that attaches to a tool holder and cleans the machine surface.

Small shop add-ons

CNCs with work areas that are less than 4x8 in size can benefitfrom relatively inexpensive upgrades and add-ons that open the machine's potential. These include aftermarket kits for milling dovetails or fingerjoints, drag or oscillating knife kits, and burning pen attachments that replace the router bit for doing fine or decorative work such as sign making and pattern drawing. There are dust boots and devices that attach to the tool and blow dust away from the cut; LED lights that attach to the spindle and illuminate the work (some larger versions attach to the bottom of the gantry); small vacuum clamps and tables that will run on a jobsite compressor; and various devices that zero out bits for depth after a tool has been changed.

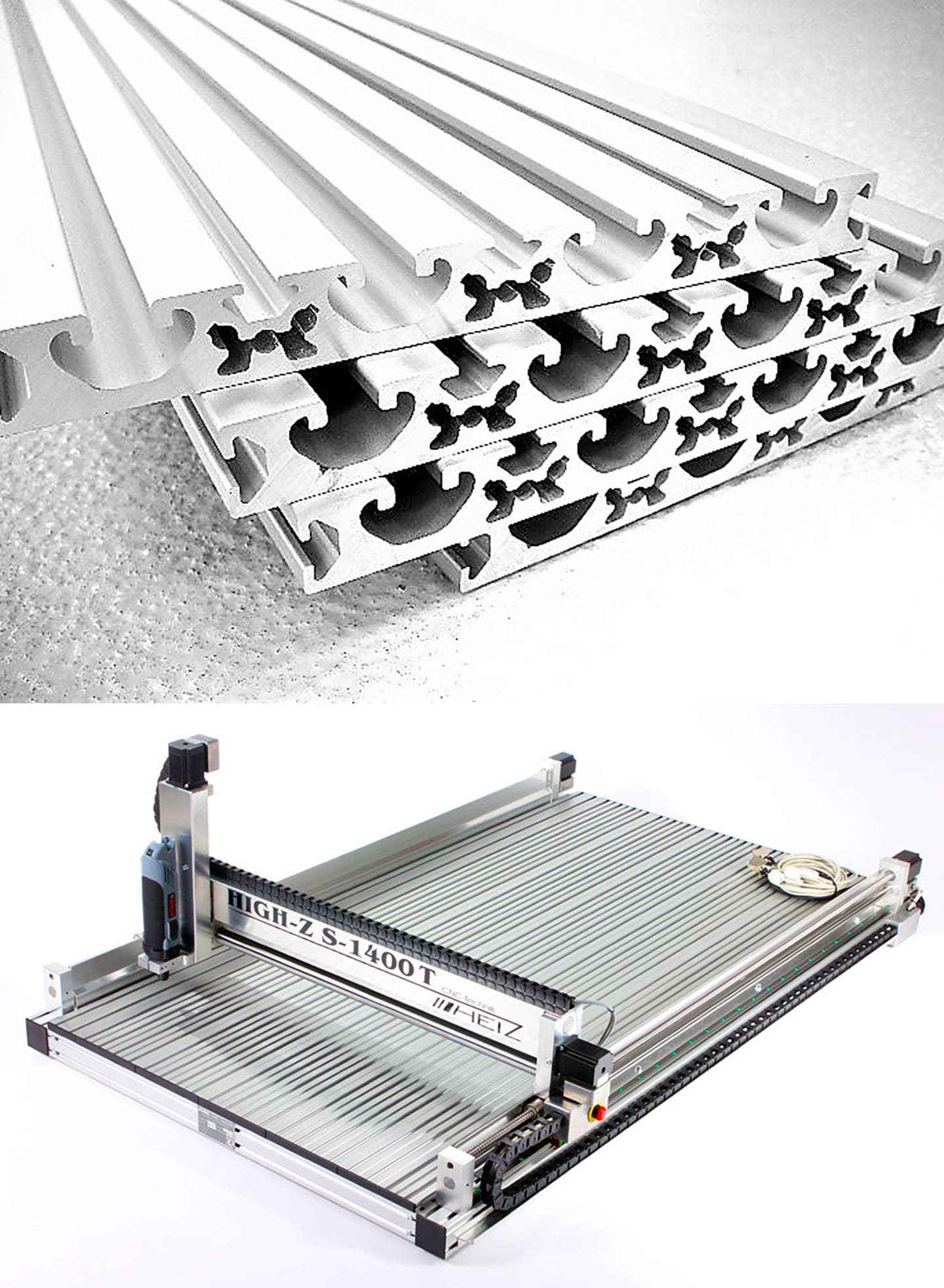

One of the easiest upgrades for a small CNC is to add a T-slot MDF table that can be used to hold work in place. The slots can travel in one or both directions across the tabletop, and several manufacturers make clamps with T-shaped bases. There are also aluminum T-slot tables, but these are usually made to fit specific models of small CNCs, and they may need to be modified if they're going to replace an MDF spoil board.

There are innumerable clamping, fixturing and work-holding devices, many of which are made of plastic or wood, so the bit won't get destroyed if there is contact. Just do a search online for "clamps for a small CNC".

Some CNCs will accommodate a 3D touch probe, which is used to create a toolpath for carving in three dimensions.

Several small CNC manufacturers offer turning kits that replicate the work of a C axis in miniature and spin the work so that the router bit can shape it. Others make small, flexible vacuum kits with a handful of pods and a single air tube that can be placed anywhere to hold unusually shaped objects as easily as they do flat panels.

Small CNCs can also benefit immensely from the addition of aftermarket spindle coolant systems, upgraded vacuum pumps, pod and rail fixturing (pods can elevate the work off the table so the sides can be accessed fully), lasers for engraving or cutting, and many other options. There are air guns that blow waste away from the tool into a vacuum system; Braille tools that can insert metal or plastic balls into drilled holes to create readable surfaces or signage; raised gantry kits that increase the CNC's capacity in Z (up and down movement), and devices that move machined parts and clean up the dust before locating the next blank.

A laser can often be switched out for the spindle, and this opens a whole new category of woodshop customers who need engraving for awards, signage, precision parts, decorative items, and marketing with logos and trademarks.

The bottom line is that older, large CNCs can be updated and upgraded for faster and more accurate productivity, and smaller machines can find new functions with relatively inexpensiveadd-ons that can keep them busy, even when the shop isn'tcutting cabinet parts.

Originally published in the October 2024 issue of Woodshop News.